9 down

Every repetition is an accretion. When Karen was four, her father told her not to make faces: if the wind changed, she'd be stuck. She was twelve when her mother told her the truth behind the lie: each line on a scrunched-up face overlays the lines that went before, and deepens them. Ration your frowns and your laughter or you'll be old before your time. So she frowns and laughs more than anyone she knows, but it's a different expression every time, never the same smile twice.

Every repetition is an erosion. The first bite of an apple is as delicious as every other bite combined. Karen leaves her sandwiches half-eaten, exhausts every suburb of its secrets and moves on; borrows CDs from each new best friend and listens through and gives them back; drops a television show the moment the audience laughs at a catchphrase. She sees her family every few years, for each new cousin or nephew, but never at her mother�s place, where nothing ever changes.

This year her new best friend is Nathan. Each time she gets another temp job she smuggles him toilet paper and stationery, and each time she loses it he buys her lunch with piano scholarship money until she finds another. She likes music students; she knows she�d never be able to bear to practice, that she never even managed "Greensleeves" on the recorder at school, so music astonishes her as a huge external force, inexplicable and overwhelming. Everything works on her, from opera to advertising jingles to bounce-beep pop in supermarkets, where she abandons trolleys to the aisles if something too familiar plays, and dawdles while she pretends to read the back of orange juice cartons when it�s something new. Being friends with Nathan (or Lori, or Alex, any of them, all the way back): it's like having access to locked doors and secret tunnels, a way in to the mysterious controls of her brain.

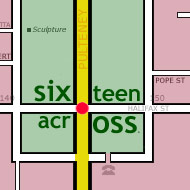

They're supposed to be meeting in the bookshop on Hindley Street, but when she walks up a sidestreet she can hear buskers, the same passage repeated twice, three times. Lori used to play it on the piano. She turns a corner and circles back into silence; there's no rush.

"You don�t say," Nathan says when she phones him to say she�s running late.

"The bus just stopped for ages, I don't know why. See you in quarter of an hour though."

"I thought you were in town already for your Zutti work this morning."

"As of yesterday I don�t have Zutti work ever again."

Nathan�s sigh comes out of the phone in a burst. "You always do this," he says, but she�s hanging up.

She leans against a wall and waits. She only heard the music for thirty seconds, but it's enough. She remembers the last time it played where she could hear it, a couple of years ago now, an ad on TV: soap or chocolate, a woman in a bath with lots of dark velvet. The time before that had been the very first: a wooden bench underneath her as she waited for rehearsals to finish; clouds, cold wind, someone throwing misshapen Smarties at her mouth from the next bench over; a late-night walk through the parklands, stumbling and laughing.

She circles in toward the bookshop, and backs away when she hits the music again. She can�t afford to keep remembering.

She doesn�t hate the past. She loves it, everything she's ever done, the tears she cried out on childhood playgrounds, the boys she kissed in other people's wardrobes during party games whose rules she never understood, the multicoloured filing system in the first of so many briefly-held jobs. It�s because she loves it that she can�t bear to dilute it. Each perfect meal can never be repeated in case she weakens the memory, each time she falls in love she refuses to let the first month of wonder be overlaid with anything else. She remembers the best things that ever happened, and never stays around long enough for the worst.

The wind changes direction, and she can hear the music again, but it�s in her head now and it�s too late to move. What is it? She remembers the context but not the name. The notes rise and fall, minute variations over and over again, never quite the same.

The phone rings again.

"Where are you?" Nathan asks. The music plays behind him; she still can�t remember what it�s called, how the patterns work.

"On the bus."

"Your bus just drove past me."

She shifts against the wall as the music falls momentarily silent, and tiny hooks in the rendering pull like Velcro on the back of her shirt. "Checking up on me?" she says.

"Didn't think I needed to. Walking up to meet you, mostly."

She hangs up. It�s a bad time to lose friends, but it�s never a good time, and sooner or later she'll have to do it anyway, so she pushes buttons through to the directory and deletes his number. It�s always a relief, once it gets to the point where she knows everything is going to go downhill.

The phone rings again so she turns it off and waits as the music gets louder, trying not to let the sunlight obscure memories of that colder night and the conductor�s baton; but when she wipes away sadness and happiness, she�s left with the fear that the next time she hears the music she won't be able to remember anything except standing here, sunlight patterning red through her closed eyelids.